Overheard: Does the sun still shine if everyone is living in a bunker underground? Translation is a process whereby words generate and decay. Me and my furry friends, anonymous plants and animals, purely penpals, are non-communicative readers communing with Lyn Hejinian’s “Rejection of Closure.” We’re caterpillaring spelunkers spending precious final days, hours, minutes, seconds, close listening to Anna via Alex dipping their wormwood-tipped pine needles in vegetable matter. Ears to the permafrost, hairs standing on end, hard-of-hearing, but this is hard to hear, and not for our ears, anyway. The ecosystem echoes their clandestine spylines. At high noon, they sneak into the pores of your skin and trip a sequence of sequences i.e. consequences. I now want to recognize (pre-cognize?) the Speaker of the House, distinguished member of the true shrew family, leader of the tiniest avant-garde, first mouse on the moon. For the Shrew by Anna Glazova trans. Alex Niemi (Zephyr Books, 2022).

Voice Notes

Adam’s at the altar telling tall tales. I am awash in this inky atmosphere, strands of wistful mystery, a rhapsody of revision as it happens. He has a wizard’s earworm, famous mouthfeel, and his sights set on the apple fell from that dead tree. Can you see him: twenty-something, counting syllables in bed, biting on bottomless coffee, skywriting behind wired eyelids. Now: handsome and charming in Cambridge, mussed with a crush, crisscrossing the country, amidst our mythical American ampersands, on a morning commute through mountainous emptiness, conjuring a family from the whirling ephemera of the world’s memory. There are lyrics to commemorate meals, seal purchases, capture love, offer prophecies. Letter sounds stretch from the heart-of-the-matter to the farthest satellite electron and then are accordion squeezed into an impenetrable Parmenidean One. It’s all a blur, obscure, gone in th’blink’v’a’twinkling’i. Voice Notes by Adam Golaski (Spuyten Duyvil, 2023).

I Feel Fine

Line! Life is a miracle and/or a mirage. A random thought balloon makes a fake moon landing in meat space. My ears popping over the bathroom sink, I think therefore I suck, I suck, I suck. You should’ve seen your face… seeing your face… seeing your face… comic book versions of yourself, a bunch of scrunchy-looking motherfuckers, on a futile mission to retrieve the exactly right words from wherever they’ve been saved… stored… stuck. Writing towards the disordered world. “How’s the patient today?” Properly medicated, nonetheless a little punchy. I stay with her and her inner editor. We play guessing games, feeling for the misplaced caesuras, copying the choppy rhythms of social interaction, naming that actor, naming that film, without even searching IMDB. Olivia Newton John. Steven Spielberg’s E.T. Whitesnake’s “Here I Go Again.” When the wheels can’t stop spinning, remember, we’ll be there, your ideal readers. Pinky swear. I Feel Fine by Olivia Muenz (Switchback Books, 2023).

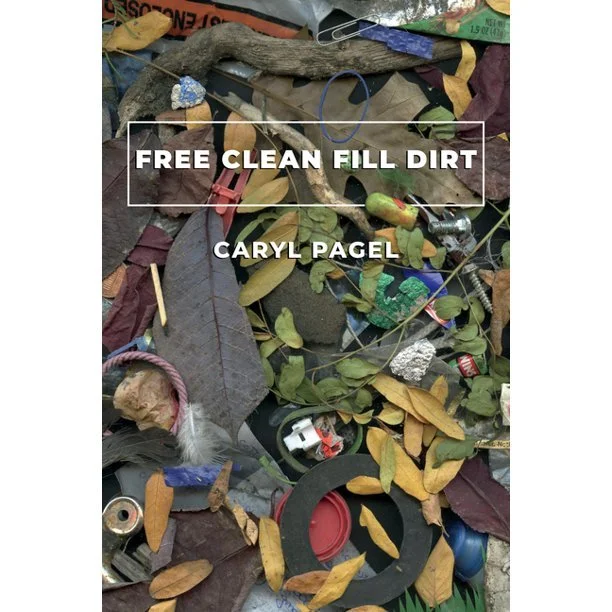

FREE CLEAN FILL DIRT

“A winter’s day,” Paul Simon sang, before having a son, before consciousness of climate change, before the hollowing of your hometown mall. All the billboards say “danger danger” or “memento mori.” So Caryl (as a coyote) pounds the Cleveland cement with a crystalline facility, followed by Emily’s Fly, Marianne’s Fish, and various background actors from The Walking Dead. Through her discerning ultrasound lens, “rock” means steady, “still” means photo, “earth” means land filled with dirt (i.e. diapers, cars, peanut butter jars). The Rust Belt is in the eye of the beholder, and we are just routine roadkill beholden, beheld, in the belly, of the belly, of the belly. As the poles melt, and cops concentrate on policing women’s bodies, gunning down Black and Brown children, she reads to tread water, and sees poems as vessels for hopeful souls. Squirreling optimism like a mother. Putting bandaids on bullet holes, one boot in front of the other. Free Clean Fill Dirt by Caryl Pagel (University of Akron Press, 2022).

Not I

“There’s no I in team,” admits LangPo academia on Naked and Afraid. “It takes two to tango,” declares the twittering virgin to the bootstrap chad. These confession statements were written by a caricature of Steinian genius in the tense of “to be continued.” Okay, let’s run the senescent sentences through a lie detector and then double-check Dictionary.com. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the non-narrator of this non-novel is a has-been who has been a have and a have-not. He’s a Buddhist Houdini with “sad charisma.” Now for the backstory, a bastion of colloquial bits, his successes and their unraveling, and the clownishly anti-climactic final act. The past: a diminishing context for “relationships” and “regrets.” The future: a petty parade of fat suits. The present: Sebastian presents us with a primer of lines to rehearse and rehearse. Know better, do better; see something, say something; hurt people hurt people; worse comes to worst. Not I by Sebastian Castillo (Word West Press, 2020).

Hole Studies

Connecticut Yankees, kangaroo courts, etc. We read by dissenting from sentences and building some banging alternatives. She with her red pen, me with my mechanical pencil, literarily critical, but referentially, citation-free. As we do, in these days of chronic despair, indentured li’l Care Bears at the downfall of Higher Ed. As we do, in the land of plenty, portaling to idylly elsewheres when the empire inevitably strikes back. Hilary reiterates her intimate connections to faraway lands like Iraq and Afghanistan and faraway eras like the early 2000s. Hilary counterfactualizes apathy, necropolitics, white America, “context collapse.” She kills this opportunity to share her complicated relationships to pop publishing, student debt, health insurance, doing dishes. “Is writing an activist act?” I picture her being interviewed on Jimmy Kimmel, slipping off-script, ripping up shit, lighting his entire set on fire. Mic drop: “Sincerity in Hell.” Hole Studies by Hilary Plum (Fonograf Editions, 2022).

Normal Distance

Stare off into the middle, of the meadow, in the rearview mirror, and say it three times, I dare you. Who am I? Who am I? Who am I? I’m Plato’s Socrates sparring with Sylvia Plath starring as all of the solipsists. I’m the tip, tip, tip of history’s iceberg, but half, half, halfway around the “Clock of the Long Now.” I’m on the wrong side of forty, afternoon drinking, with a bevy of fact-snacks and a penchant for the absurd suffering of words. I said “suffer,” but meant “torture.” I meant “aphorism,” but thought “axiom.” I can’t think “ideation” without thinking “suicidal.” I’m a wizard news-watcher talking myself in and out of profound panic. I’m a Barthesian who can lower his heart-rate by increasing my jouissance. I’m wrestling’s The Undertaker listening to classic Townes Van Zandt’s “Waiting around to Die.” Every supposition starts “Alas, poor Yorick” and ends IYKYK. Just ask Elisa. She’s the rightful heir to the magic 8-ball and master of disaster of the internet of things. Normal Distance by Elisa Gabbert (Soft Skull Press, 2022).

Disbound

First friend, second language, third world, and so forth. Who counts and who does the counting? Hajar’s mission statements are scraped-together-scraps of meta-etymological Moleskin interspersed with gracefully tear-stained endpapers. Homeward here is less a direction than an orientation towards broadcasting the collective subject’s “Other News” — from bed — in what amounts to a Best Western. She somehow brings herself to Facetime NATO with a procession of “close distant” lowercase poems. This one-woman show infiltrates the panopticon, then goes clothes shopping at the mall, tries on a range of contemporary forms, mixes and matches, syntax and prosody. It’s a coping strategy: to keep hope, but not be co-opted by capitalism. So her slashes tilt to the left, her apostrophes dispossess, her lips… ellipses… peopleless, and her lines break every which way. Yet, look, the poet is living, hurrah, and the book is binded by her spine. Disbound by Hajar Hussaini (University of Iowa Press, 2022).

A Boy in the City

Fuck nature. Post-coital, but pre-deep sleep, chest heaving, S. tells us a few breaking bedtime stories. Like when Little Bo Peep’s childhood fell into a Blakean black hole. Or when Babe of the barnyard guest starred on Sex and the City and stole every scene. He’s a pretty boy prince born to be horny, a knight errant on blue errands (by blue, I mean, slightly pornographic), a Batman-style vigilante who can best his enemies with Latin cognates, and a private detective, aka dick, codename Dada Baudelaire, who voyages nightly to the darkest bar in the theater district. Neck-tied and live-wired. Picking up bad birds. Let’s share our bodies like works-in-progress. The page is where we are free to explore and experiment. Do you want to go back to my nest and undress the origins of desire? While outside these poems, wild dogs bark and sirens blare, I’m inside them, furiously self-reflecting, sucking on air, telepathically texting S. the fire emoji. A Boy in the City by S. Yarberry (Deep Vellum, 2022).

pilot

From a sea of bodies, “you” and “I” are somehow cast as castaways in the test run of primetime meets Nietzsche’s eternal return. I’m a walking-talking disaster destined to share my screen with Jack Spicer’s splice queen backslash the Tin Man’s polar opposite. We’re strangers-in-a-strange-language having an old-fashioned staring contest. Come in for a hypnotic close-up. Then flashback to a crash that was always going to happen. It’s all here in the transcripts: plot amnesia, unraveling interludes, semantic playstation Doomerology. Poetry’s been dead since An Essay Concerning Human Understanding – you heard? – but nonetheless – there’s a secret network of survivors watching us watching them collect text like cold cash from abandoned ATMs. Here’s a couple of meaninglessly meaningful pull quotes. What’s a word that precedes “the damage”? Examine. What’s the word for reading a poet reincarnate as a TV show? Great question. Not sure the creator even knows. Pilot by Danika Stegeman LeMay (Spork Press, 2020).

There Must Be a Reason People Come Here

How many ways can you destroy a flower? How many ways can the days break? Hear the “association” in free association as a welcoming to get shot in the backcountry where naked means plain and anarchy means mundane brain activity. Post-confessional, post-HR visit, I feel kinda clean like walking into the Fresh Market and wanting to burn it down or punctuating the world’s abundant wonders with the words “not / so much.” Divine is a noun and a verb. Miracles are regular things: the ground, an egg, a cigarette on your work break, medicine for your chronic ambition. To be neither necessary nor sufficient – yet still – have a willingness to pen “standalone” poems while relentlessly maintaining a tone that’s just “difficult.” It’s called integrity, Hamlet. Try qualifying practice: nearly missed, momentary relish, holding each other responsible. Fine, I’ll go home now and hate watch the latest highly touted average palaces. See what all the fuss’s about. There Must Be a Reason People Come Here by Brian Foley (Black Ocean, 2021).

Action in the Orchards

Writing about the poet writing about art to be a party to Dead Fred’s guided tours. As we go pre-and-post-ing through history’s revisional -isms, he documents Documenta bric-a-brac, photo-painterly foliage, quaint antique knowledges. Be you a red-cheeked knight riding the bypasses of medieval Europe or O’Hara’s avatar on a chance nature walk in the 20th century’s countryside. Sometimes you pick an apple and put it in your pocket. Sometimes you kick it back into the branches like a football. Sometimes it falls, hits you square on the Newton, practically decapitates you. I start roller skating fast and carrying, in one hand, an umbrella (like Magritte’s that balances a glass of water), in the other, a camera (that can point only at my own overgrown face). See me seeing the plastic littered everywhere in this pie-on-the-sill pastoral and trying manically to shove it all into a suitcase. Hear my interiority microphone saying: “This was a good book even if it don’t matter.” Action in the Orchards by Fred Schmalz (Nightboat Books, 2019).

THE EMPTY SEASON

What can you sing when everything’s in boxes? Packing up the song of myself. It’s the day after New Year’s, and I’m already-ready to restart my restart. Cutting and pasting antidepressant martinis with a little anesthesia of the third person. She pictures the house through filters like “distant past,” “Jesus etiquette,” and “foxnewsforever” and remembers what it felt like to love a president the way a child loves her parents. Fast forward to a midcentury modern middle-of-the-night under a thick blanket of snow. Talk talk talk me to sleep, she says, count the she-she-sheep riding an elided Brooklyn Ferry (see: Wikipedia). So sick of being inside a body forced to move out into the boring well-intentioned world beyond the bedroom door. But does writing poetry have the efficacy to be headline therapy or heart medication? This is me asking. The dude-poet reading Catherine’s book, spitting daylight in a gas mask, watching his hair turn white. The Empty Season by Catherine Bresner (Diode Editions, 2018).

Plans for Sentences

The old electricities feel shittier in a manifold kind of way. So now it’s time to think about what we’ll do next. Let’s assemble in this unknown sanctuary between worlds, link tiny antennae, and listen insistently to weather reports from the threshold. As we sit wall-eyed, and bellowing, and meaning to breathe, here are some desk reminders. The gender of a sentence is always they/them. Beginnings and ends have cross-sections and flip-sides and possible past and future tenses turned inside-out and outside-in like a crystal ball. We’re only ants skipping along infinity-laned micro substrates, the shorelines of a thinly skywritten invisibly-inked sea, into our eventual interdimensional hidey-holes. Perhaps together we can brainstorm littoral housing projects, blacken the castles, or recontextualize the relentless political fog bath as enlightening white space. Put everything back in its right place, but on a new planet. The poet has drawn us some diaphanous maps. Plans for Sentences by Renee Gladman (Wave Books, 2022).